The True Origin of the Spanish Influenza

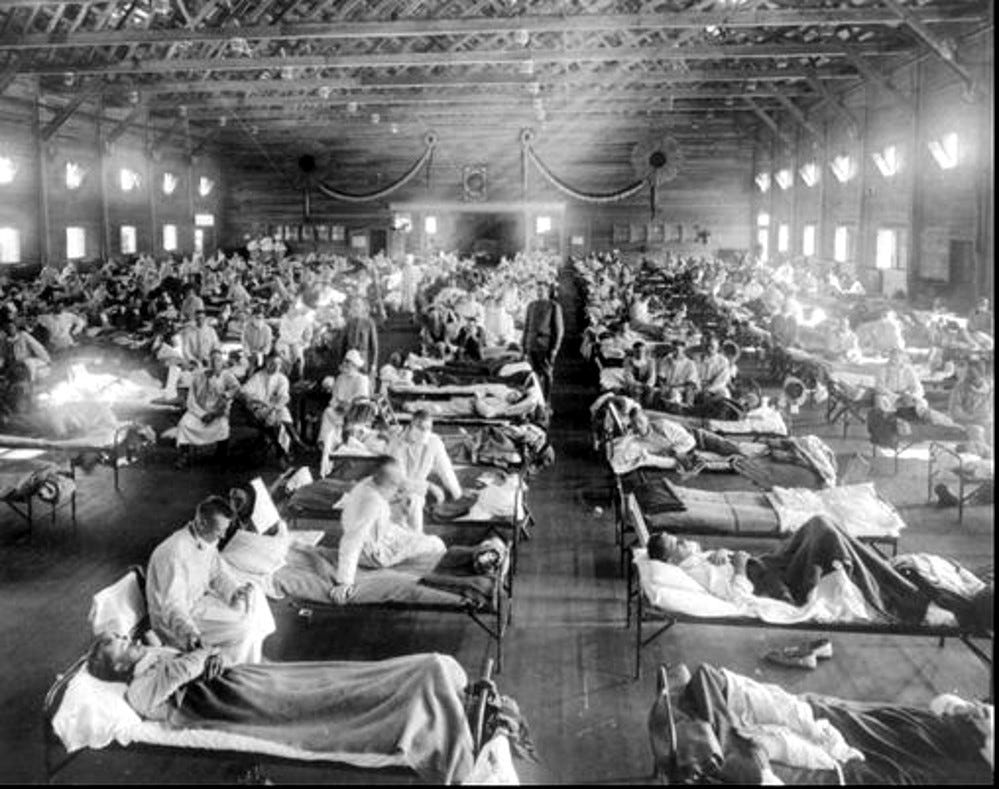

Over 100 years ago more than a third of the world's population, about 500 million souls, were infected with a deadly disease that could kill them within the first 24 hours.

Of those infected 50 million did die, and strangely this illness targeted young adults versus the aged or children.

In World War I, neutral Spain was the first to report flu deaths in its newspapers, so commentators soon nicknamed the pandemic ‘Spanish flu.’ It was also known as La Grippe Espagnole, or La Pesadilla.

Despite the belief that most of those who contracted it died, this was not the case.

In 1918, it was described as a contagious kind of "cold accompanied by fever, pains in the head, eyes, ear, back or other parts of the body, and a feeling of severe sickness. In most of the cases the symptoms disappear after three or four days, the patient then rapidly recovering; some of the patients, however, develop pneumonia, or inflammation of the ear, or meningitis, and many of these complicated cases die."

This was not the first time the country had experienced some type of epidemic that came from foreign shores. In 1889 and 1890 an epidemic of influenza which started somewhere in the Orient, spread to Russia and then to the "entire civilized world." There was a flare-up three years later, and both times the epidemic spread across the United States.

Even as early as 1918, the misnomer of "Spanish influenza" was questioned since it was believed the true origin of the flu was from the Orient and not Spain, or from the filthy trenches in France. It was mentioned that Germans described the disease as occurring along the eastern front in the summer and fall of 1917.

The Spanish flu didn't occur only in the winter months but in the summer months as well.

Ordinarily, the fever lasts from three to four days and the patient recovers. But while the proportion of deaths in the present epidemic has generally been low, in some places the outbreak has been severe and deaths have been numerous. When death occurs it is usually the result of a complication.

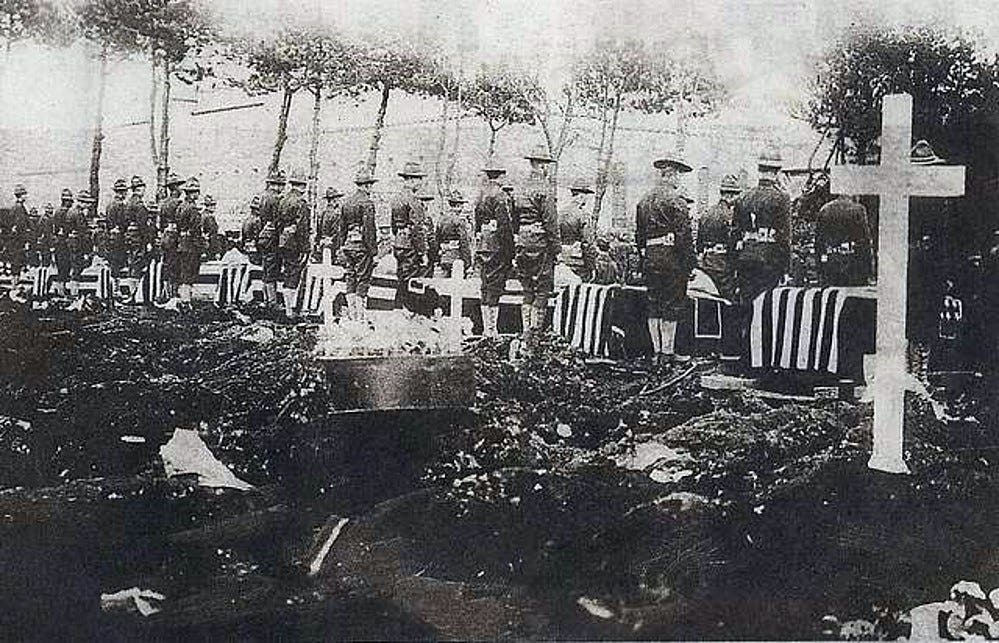

Like in earlier periods of numerous deaths, morgues and gravediggers were overwhelmed, not only by the high numbers, but because many refused to work due to fear of contagion.

The disease killed more American troops than those that died on World War I battlefields. Americans had joined the fight in 1917, bringing the Allies ever closer to victory over Germany and the Central Powers by the spring of 1918.

For decades the origin of this modern day plague remained a mystery, however new research is placing the flu's emergence in a forgotten episode of World War I: the shipment of Chinese laborers across Canada in sealed train cars.

Canada's Memorial University of Newfoundland claims that newly unearthed records confirm a formerly ignored story from this time period. This concerns the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines on World War I's Western Front. It’s believed this was the true source of the epidemic, and might have brought an ending to the war.

The Spanish flu killed a much lower percentage of the world's population than the Black Death, which lasted for many more years. It started in the spring of 1918 and lasted until January of 1920, infecting 500 million, but killing 50 million people. The Black Death killed somewhere between 47–200 million people, primarily in Europe and Asia, but it lasted from from 1347 to 1351.'

Out of the 50 million that succumbed to the illness worldwide, about 675,000 people lived in the United States. This was about 1% of the world total who died.

An outbreak of respiratory infections, which at the time were called endemic “winter sickness” by local Chinese health officials was found in records of that time by researchers. A year later Chinese officials identified the disease as being identical to the Spanish flu. It caused dozens of deaths each day along China’s Great Wall. The illness spread 300 miles in six weeks in late 1917. China suffered a lower mortality rate from the Spanish flu than other nations did, suggesting some immunity was at large in the population because of earlier exposure to the virus.

New reports finds archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu. Also found were medical records indicating that more than 3,000 of the 25,000 Chinese Labor Corps (CLC) workers who were transported across Canada en-route to Europe starting in 1917 ended up in medical quarantine, many with flu-like symptoms.

This Chinese work force was recruited by the British government during WWI to perform manual labor, thus freeing troops to respond to the front lines. It was formed in 1916, and consisted of about 140,000 Chinese men who served in France and throughout Europe. The journey to France took three months, and most laborers traveled to Europe via the Pacific and across Canada.

A British legation official in China reported in 1918 that the disease originally thought to be pneumonia was actually influenza. This information was found via searches of Canadian and British historical archives that contain the wartime records of the Chinese Labor Corps and the British legation in Beijing.

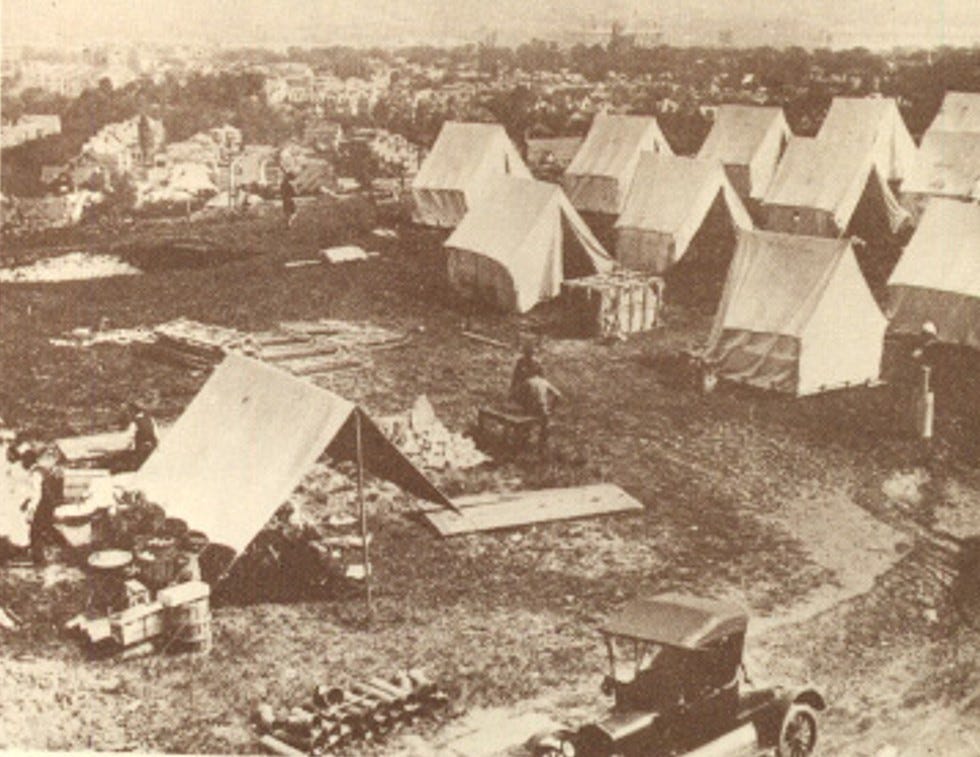

Once the outbreak of influenza was noticed in China it stopped the recruiting but the need for workers was so dire that they were still shipped in sealed train cars across Canada, and newspapers were banned from reporting on their movements.

The Chinese laborers arrived in southern England by January 1918 and were sent to France, where the Chinese Hospital at Noyelles-sur-Mer recorded hundreds of their deaths from respiratory illness.

Historian James Higgins, who lectures at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and who has researched the 1918 spread of the pandemic in the United States said, "I would say that the takeaway message of all of this is to keep your eye on China" as a source of emerging diseases.

The final debate on the origins could be settled with tissue sample from the time period before the onset of the epidemic, in 1916 to 1917, which so far has not been found in any burial sites.