The Revenge of the Miner's Ghost

He was dismembered, burned and buried so no one would be the wiser of what truly happened to him. But his ghost refused to leave the nature of his death undiscovered, & the real reason he was killed.

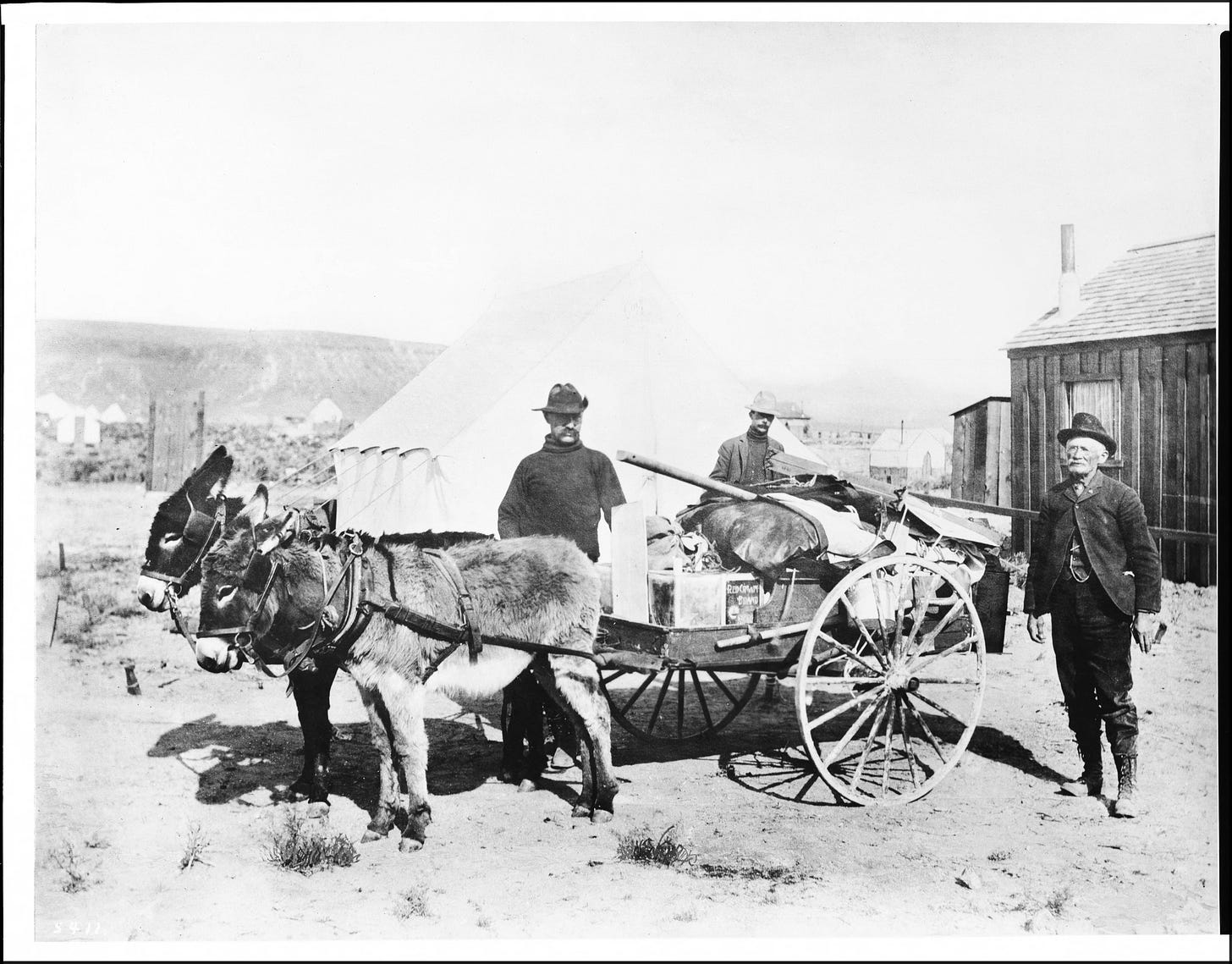

Carlin was a small town, a stop on the route of the Central Pacific Railroad. Established in 1868, it wasn't long before it connected freight and stage routes to the railroad. It thrived, and by the 1870s almost a thousand people lived there. It had a two-story brick school house, a library, a Chinatown and several small businesses.

Right around the time an ice-harvesting industry grew in Carlin, a murderous crime was discovered.

It was June 20, 1890 in Elko, a mining town in northeastern Nevada, a place and time when justice was served swiftly, however this date marked the first and only time a woman was executed in the state. Sharing the specially made double-gallows with her, was her husband. It had been constructed in Placerville, California and shipped to Nevada.

Their names were Josiah and Elizabeth Potts, and their crime was the murder of Miles Faucett, 57, a neighbor and miner, who like the Potts had left England seeking his fortune in America.

They married in 1863, and arrived in the United States in 1865. They had a total of seven children together, but five of the children were adopted out to various families throughout several states for unknown reasons.

Josiah Potts worked for the Central Pacific Railroad, and left Milwaukee with his wife and seven children to relocate to Carlin, Nevada. By the time of the crime, only two children were living in the household, Charles, 16, and his sister Edith. Whatever served as the impetus for the move is unknown, but the family wasn’t awash in money, which perhaps is what led to the crime.

Elizabeth Potts was a large woman, estimated to weigh about 200 pounds at the time of her hanging. Her husband was quite the opposite. He was physically smaller than her, and had a timid personality to go with it.

Known as “Old Man Faucett” the miner lived on his small spread known as the Hot Springs Ranch situated on the outskirts of Carlin. When he visited Elko he would board at the Potts home, where Elizabeth washed his clothes and cooked his meals for a fee.

During the trial it was confirmed that little was known of the Potts before they arrived in Carlin, however Josiah Potts was a quiet man and master of his trade as a machinist. He was well-liked by his employers and his neighbors, however Elizabeth was known to make long trips to California, from "whence came rumors of a fast life, and when at home was more or less addicted to the use of liquors and quarreled with her neighbors, who bore her no love and generally let her alone."

Upon her return from one of her trips to California, Miles Faucett appeared in the town. It was supposed he made her acquaintance there, and had followed her to Carlin. This happened about a year before he died. Before he moved to his ranch he boarded full time with the Potts.

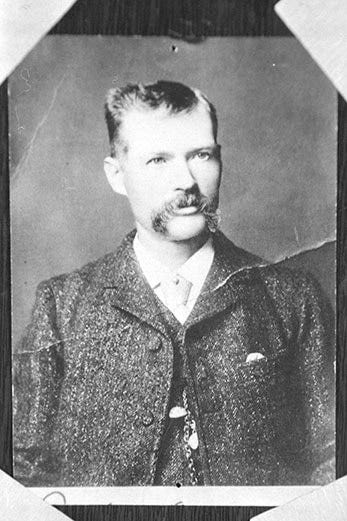

On New Year's day of 1888, Faucett left his ranch and came to Carlin. He was keeping company with a man named Lineberger. It was a cold and stormy night and Lineberger urged him stay with him instead of returning home.

Mrs. Potts invited him to stay with them and he accepted.

He left with Lineberger to feed his horses for the night and paid him $5, and Lineberger saw he had $100. Fawcett told him that Potts owed him quite a lot of money, and he would not have stayed at their house, but he knew Mrs. Potts was preparing to go to California, and he thought that if he didn't get his money that night he would never get it.

Lineberger told him to attach Potts' wages. Faucett's reply was, "I will not attach his wages, but I will get my money. I know something on her that will hang her, and I will get my money without any suit."

That was the last seen of Faucett.

Lineberger subsequently bought the house from Potts for $150. A couple of days later Mrs. Potts and the children left for California, and Josiah remained there for some months and finally moved to Rock Spring, Wyoming where the family joined him.

The Potts’ unoccupied house was rented to George and Amelia Brewer. Amelia who worked for the Elko Free Press, and who considered herself a psychic wrote the following on January 5, 1889:

I have intended to write you for several weeks, but when one moves to a new place one naturally is kept very busy for awhile… It is a little exciting when one has the good luck to move into a veritable haunted house. So far, the ghost hasn’t scared any of us, but he is here just the same. Sometimes he taps on the headboard of the bed, other times he stalks across the kitchen floor and then he hammers away at the door, but nobody’s there. But the gayest capers of all are cut up in the cellar. There he holds high revels, upsets the pickles, and carries on generally.

In a quest to lay the ghost, George Brewer dug up the cellar with an iron rod, and found what was left of Faucett. The head was gone, or only a piece was left which was charred and fleshless, one arm was gone, both legs were off and the body had been cut in two above the hip. The official report said the “The only clue to the body’s identity…was the half-burned pocket of the murdered man’s pants, in which was found an old knife…recognized as belonging to Miles Faucett.”

Sheriff Barnard and Constable Triplett were soon headed to Wyoming looking for their prime suspects, Josiah and Elizabeth Potts. The couple was arrested and on their way back to Carlin, Nevada, they told the sheriff that Faucett killed himself after Elizabeth found him abusing their daughter Edith. Faucett had also turned on her, before putting a bullet in his brain. Afterward they cut up the body, fearing they would be charged with murder. Josiah attempted to burn it, but the smell was so bad he just buried what was left of the man.

On February 13, 1890 the pair were indicted for murder, and pled not guilty. They were tried in Elko before Judge Bigelow, found guilty and sentenced to death. Upon hearing the verdict Josiah bowed his head, but Elizabeth looked straight ahead with an expressionless face, but she did cry when she returned to her jail cell.

During the trial, Charles, 16, and Edith, 6, gave conflicting accounts and some wondered if they had been coached in their testimony. Edith said it was her mother who killed Faucett, and that her dad was not at home.

The Supreme court of Nevada upheld the decision, and only the Board of Pardons could have commuted their to sentence to life imprisonment. The citizens of Elko circulated a petition, which was generally signed asking for a commutation to spare their lives. In the end the board did not save them.

On April 25, 1890 they were resentenced to be hanged with a date set for June 20, 1890.

Charles Potts, 16, left with a friend to Oregon, and changed his surname to Atherton which was his mother’s maiden name. He did well for himself and became a wealthy man. He owned the famous Blue Bird Tourist Company in Washington. His sister Edith, 5, remained behind with her parents, and was adopted by a couple living in Carlin.

The day before the execution Elizabeth Potts slit her wrists with a small penknife she had hidden in her hair. When her attempt was thwarted, she “cut up fearfully” and then fainted.

One of the jailers gave the couple a small bottle of “reinforcing tonic” (assumed to be whiskey) to help ease their anxieties. Elizabeth was dressed she had ordered for her execution which was white with black silk bows at her throat and wrists. Josiah wore a business suit.

Both of them maintained their innocence even when they were standing on the gallows. Contrary to reports that Mrs. Potts had been decapitated since she was so heavy, the stream of blood that came from underneath her hood was due to her carotid artery being broken by the rope.

The Potts were then taken side-by-side to a potter’s field and buried, ironically, near Miles Faucett’s remains. Josiah was 48, Elizabeth, 44.

Many years later, Howard Hickson—at the time director emeritus of the Northeastern Nevada Museum in Elko—reported the following: “Several years ago, I interviewed Charles Paul Keyser, then in his nineties. He was a teenager when he [shinnied up] a pole to watch the hanging. After he told me the story of the murder and trial, I asked him, ‘This couple was convicted pretty much on circumstantial evidence. Do you think they were guilty?’

He blurted: “Hell, yes! Everybody knew they did it!”

Two months after the execution a story started to circulate that Miles Faucett (Fawcett) had married Elizabeth Potts under the name of Elizabeth Atherton in San Francisco in March, 1887.

A reporter from The San Francisco Examiner found a marriage license was issued on March 29, 1887 for Miles Fawcett and Elizabeth Atherton, listed as a widow. They were married that same day by a justice of the peace. There was only one witness named Lizzie Thomas.

After the marriage Faucett had Wickliffe Mathews, an attorney investigate her background as he believed, "all was not right." He told the lawyer that he paid Lizzie Thomas a marriage broker, $105 to get him a wife, and that he had married the woman supplied. The lawyer told him his new wife had a husband named Josiah Potts living in Carlin.

Fawcett planned a suit to recover his money, and the $105 was returned. However it seemed that Mr. Faucett was in love with his new bride, and dropped the legal proceedings against her and took her to his home near Fresno. Afterward he followed her when she returned to her husband at Carlin, which is why he sold his property in California, and brought a place close to the Potts family so he could be near her.

Now some wondered if the true motive for the crime was her fear he would disclose she was a bigamist. Supposedly Faucett had blackmailed her about disclosing this information. Later Judge Reardon from the San Francisco Superior Court said that if she had provided this information about her illegal marriage, it would have the saved the couple from execution.

Another mystery which lingered and was never fully explained was why the Potts did not keep all their children. This is what’s known of some of them: There was George Bush (Potts) (1868-1935) born in Chicago; Ida Potts (1877-1939) spent her life in Utah adopted by the Taylor family; Frank Potts (1881-1931) born in Stillwater, Minnesota and died in Washington.