THE PRICE OF DISOBEDIENCE AT THE CHURCH OF SACRIFICE

In January 1911, 605 Western Avenue in West Crowley, Louisiana was the scene of a horrific murder of an entire family.

Officer Ballew, the first to arrive found Walter Byers, his wife and small son all lying in bed with their skulls split wide open.

The sheets underneath them were drenched in blood. The front door was locked which indicated the murderer had entered through an open window. There was no need to search for the murder weapon since in a corner of the room next to the head of the bed, was a bucket full of blood and a bloodied ax propped next to it.

The local newspaper called it "the most brutal murder in the history of this section", and at the start of the 1910s, the murders blazed a path of terror through a cluster of towns along the Southern Pacific railroad line.

Some believe the first crime was the murder of Edna Opelousas and her three children, killed in Rayne, Louisiana, in November 1909. They had been decapitated and dismembered.

The Byers family were the next to be dispatched in January, 1911

In February, 1911, inside a cabin in Lafayette, Louisiana another family was slaughtered. Crime was no stranger to the poor part of town but Sheriff Louis LaCoste and Deputy Coroner Clark were surprised at the brutality of the killer's handiwork.

The bodies were posed. Both were propped on their knees with Mimi Andrus' arms draped over her husband's shoulders as if in prayer. Their two small children, Joachim and Agnes, were laid in front of them on the bed. The sheets were red with brain, gristle and gore.

Dr. Clark found the bodies were still warm, placing their death close to midnight. The perpetrator had come in through the kitchen door, and left the same way.

Lezime Felix, Mimi's brother had found them around 7 a.m.

The only lead was Garcon Godfry, an escaped lunatic from Pineville, less than 80 miles from Lafayette. They eventually brought him in and returned him to the asylum. They were, however, unable to connect him to the murder as Godfry’s whereabouts had been thoroughly accounted for. Further arrests were made, but they came to naught.

Soon other similar crime were committed in Texas. Halfway between New Orleans and Houston, the railroad had changed Lafayette’s fortunes, and the Southern Pacific now appeared to be tracing a blood-red line from Cajun country to the Lone Star State.

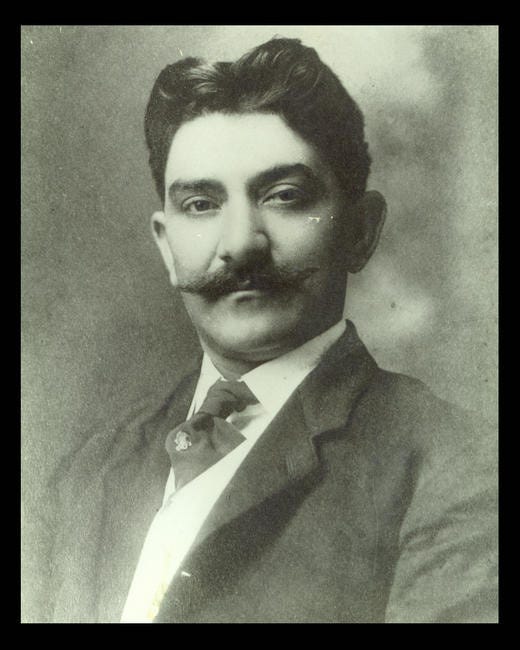

One of the leads that police followed led to Raymond Bernabet (Barnabet), a sharecropper and petty thief who lived in the rundown side of Lafayette. The family moved to their current home from St. Martinsville in 1909. The surrounding area of Lafayette and Opelousas had been settled in the 18th century by the Acadians.

The lead came from his mistress Diana, when she complained about him to a friend after they had a fight. She suggested there was a connection between him and the murders.

During his trial in October 1911, Raymond's children, Zepherin and Clementine Bernabet, testified against their father, and the teenage Clementine told a graphic story of her father returning home one night with blood on his clothes as he threatened the family.

Zepherin confirmed the story, adding that their father bragged that he "killed the whole damn Andrus family." Both children said they feared for their life if their father was free. Raymond was a violent man, who beat their mother Nina Porter, as well as his children.

While Raymond Bernabet cooled his heels in jail another murder was committed on November, 26, 1911. Norbert Randall, his wife, their three children and a nephew were killed with a blow behind the right ear with the reverse of the blade. For good measure Norbert was also shot in the head. Their 10-year old daughter who spent the night at her uncle's house was spared and the next morning found the slaughtered family.

While Raymond Bernabet might have a good alibi for the crime, his daughter Clementine did not when she was found near the Randall home. Her blue and white dress was covered in brain and blood.

Lafayette Parish Sheriff Louis LaCoste, who was already suspicious of Raymond’s children, arrested them both. His suspicions stemmed in part from the fact that they had bad reputations around town; during Raymond's trial, their neighbors, the Stevens family, described them as “filthy, shifty, degenerate.” And there was another detail that concerned LaCoste: When police came to the Bernabet residence to arrest Raymond, blood from the Andrus murders had been discovered on Clementine's clothes. She testified during her father's trial that he had wiped the blood there, but the sheriff wasn't so sure.

Zepherin provided an alibi for the night of the murders, but Clementine was hauled off to jail.

Her protests of innocence later turned into an admission she had killed the Randall family with the help of accomplices in order to ‘try out’ a Voodoo charm (acquired from the splendidly named “Hoodoo doctor” Joseph Thibodeaux) they believed would protect them. This story changed a third time, with the axe-woman blaming her father and brother. Then the story changed a fourth and final time by the time she took the stand, she absolved her father and saved him from a death sentence.

Ohio’s Mahoning Dispatch wrote:

With screams of hysterical laughter the girl rocked back and forth in the witness chair, her great eyes rolling into the back of her head, barely any pupil showing. Amidst sharp commands from the court and quick questioning of the prosecutor, the woman told of how because the Randall family had refused to obey church orders she had crept upon their cabin late on Sunday night with a keen-edged axe concealed in the folds of her cotton wrapper.

”She told of how after she had thrown open the door of the tiny cabin she crept upon the sleeping husband and wife and before either could arouse had split their skulls in twain with her death dealing implement. She told how the four children on the floor started to cry out and how stealthy tread she approached their trundle beds and swinging her axe killed two with one blow and then lay about her with quick swings hacking the bodies of the two remaining children until they were scattered in bits about the room.

As she completed the awful tale, she rocked to and fro and then said: ‘An’ judge, thet ain’t all either.’

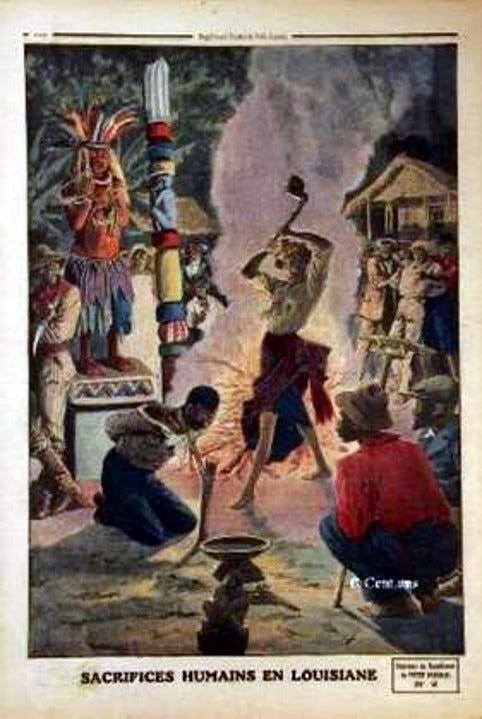

The next confession involved the Andrus family who lived in the lonely section of the parish near the Mississippi River. They had refused to obey the message from God supposed to be the utterings of a Voodoo doctor who was visiting in the district. “She with other religiously crazed [black] fanatics went to the Andrus cabin in the dead of night and there with axes hacked the sleeping members, four in number, to pieces, ending their bloody orgy with weird prayers and incantations.”

Norbert Randall was the brother-in-law of Alexandre Andrus, and both families had been present at the Church of Sacrifice. The murders themselves took place on Sunday nights presumably after the worshippers had worked themselves into a religious frenzy at their meetings.

That Bernabet had directed the murders as well as participated in them accounted at least for the differences in execution, from the neat surgical bludgeoning to the brutal bloodletting. And it also accounted for the fact that the murders continued after her arrest.

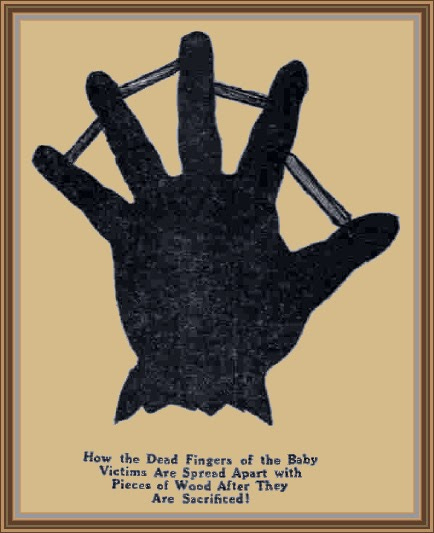

In January 1912, Felix Broussard, his wife and their three children were slaughtered in Lake Charles, a town further out along the line through Rayne and Crowley. This was reminiscent of the Andrus murders for its elaborate staging, and like the Andrus murders it dripped with dark magic.

The Broussards were found laid out across the sheets each skull crushed by the blunt of an axe. The weapon itself left under the bed.

The scene was strangely bloodless, the victim’s gore collected in a bucket as it left their bodies, but the most unsettling detail was their hands – each finger had been separated held splayed apart with wooden pins and rolled up pieces of paper.

Written above the door were the words “Human Five” and on the wall a Biblical passage, bastardized from Psalm nine: When He maketh the inquisition for blood He forgetteth not the cry of the humble.

The newspapers seized on the idea that the murders were connected to a Voodoo ritual. One of the first to take that angle, the El Paso Gazette, published a story on the Broussard murders titled "Voodoo Horrors Break Out Again."

The story suggested the crimes were connected to human sacrifice that took place as part of a Voodoo ritual, and emphasized the idea of the number five as somehow having ritualistic relevance. “Two months ago, six members of the Wexford family perished at the hands of the fanatics but one was an infant that had been born only the day before the tragedy and in all probability had not been taken into consideration when the plans for the human sacrifice were consummated," the reporter for the paper wrote. "Now comes the Broussard tragedy with its five victims, thus completing a series of sacrifices of five separate families, each evidently intended to have involved five victims.”

Around the same time, rumors were swirling that Clementine was the leader of some kind of cult called the "Church of Sacrifice," which was supposedly led by one Reverend King Harris, a Pentecostal revival preacher with a small congregation connected to the Christ Sanctified Holy Church.

Police took Harris in for interrogation after rumors of religious involvement ran rampant, but the reverend had never heard of a "Church of Sacrifice," and was visibly shaken to think that his sermons could have possibly inspired a series of bloody ax murders.

As far as Lake Charles was from Lafayette, Beaumont was from Lake Charles. On February 19, 1912, the bodies of Hattie Dove and her three children were left piled almost naked on the bed, each one slaughtered by axe-blows to the head. Unlike the others though, Dove had put up a fight and there were signs of struggle in the shack.

According to the Beaumont Enterprise “furniture had been overturned and the bedclothes had been torn from the bed, while blood was everywhere.”

In April, 1912, Alfred and Elizabeth Cassaway along with their three children were murdered in a similar fashion. Nothing was stolen and the bodies had been neatly, almost lovingly, arranged on the linen.

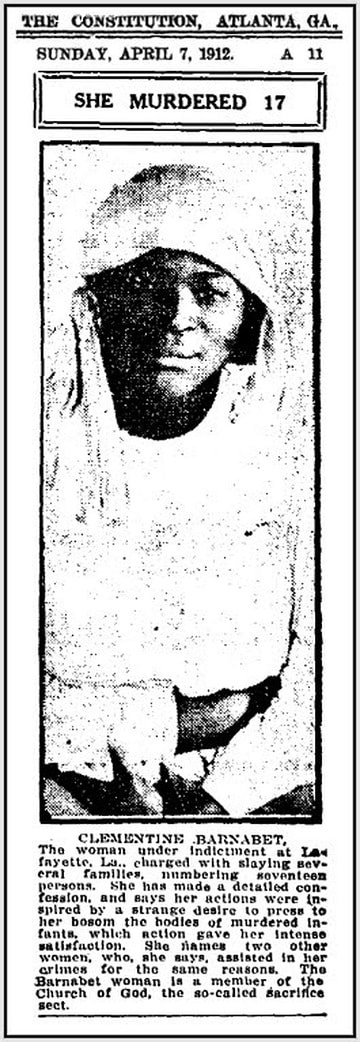

Eventually, investigators would get at least some of their answers. On April 5, 1912, Clementine made a full confession, admitting to 17 murders. She claimed she had bought a voodoo charm meant to protect her while committing her crimes, and said that she and her accomplices drew lots to see who would commit the murders. She also said that she disguised herself as a man to better lurk unnoticed at night.

The Daily Picayune noted that "she declared she killed the children because she did not wish them left orphans in the world." Her motives for the crimes, however, were never made clear.

The Lafayette Advertiser printed her full confession in the paper on April 5, 1912, but added at the end: “Clementine’s confession has been received with varying shades of belief owing to the positive way she swore in the trial of her father, and the misleading information she has given as to her accomplices.”

Indeed, it was difficult to keep Clementine's story straight. She had previously testified in court that her father was the dangerous man behind the murders, but they kept happening. She gave names for her accomplices, but when Sheriff LaCoste investigated them, they went nowhere. Several arrests were made, but the search for the rest of the “Human Five Gang” was a dead end.

The district attorney, Howard E. Bruner, theorized that some of these murders were copycat crimes, but he believed that Clementine was a "moral pervert" who was guilty of everything she confessed to. Clementine had admitted to "caressing" the corpses after she had killed them, regardless of their gender or age.

Despite investigators’ suspicions regarding Clementine’s confession, the stories about her continued to circulate. Bruner officially filed charges against her on April 14, 1912. While she sat in jail, she confessed to a total of 35 murders, but kept re-telling her story with differing details that make it hard to know the truth.

May 1912, in Glidden, Texas located between San Antonio and Houston was the scene of the next murder. Ellen Monroe, her four children and her lover Lyle Funancune were snuffed out while they slept. The bodies were found at 7 a.m. by Monroe’s fifth child Parthenia, who lived with her grandmother. Monroe and Funancune apparently survived the first blow, their bodies found by the bedside rather than in it.

Then another family of three, their names unknown, lost their lives in Hempstead, Texas.

Sheriff Bruce Mayes and a pack of bloodhounds traced the killers tracks to the home of Jim Fields. That morning while Parthenia Monroe howled in grief, Fields had washed his shoes and bought rail tickets to Flatonia, Texas, 32 miles from Glidden. He was carrying a suspicious quantity of cash and his jacket was flecked with blood. His recently scrubbed boots matched the prints at the scene perfectly although the charges were later dismissed.

It looked as though a pandemic of axe murder was sweeping Texas and Louisiana. Black communities held panicked meetings in courthouses, young black women working as servants began sleeping in their employers’ kitchens rather than return home, men began to acquire guns and rig up ‘alarm systems’ of fishing line connecting door knobs to toes.

The Utica Saturday Globe reported, "Every cabin door and window is locked and barred and no family sleeps without a guard. Every ax, every piece of iron, everything which might be used as an instrument of murder, is picked up and carried inside".

The church disbanded soon after the murders, taking all hope of clarity with it and forcing contemporary investigators to cast the net wider.

The real death toll is enshrouded in mystery, as murky and folkloric as the beliefs that inspired it. Some journalists recorded that as many as 300 may have been slain by the sect in its various guises over a six year period, drawing a veil of terror down on the black townships of Louisiana and Texas, and bringing the beat of voodoo drums into the ashen-faced conversations of a middle and upper class that would sooner forget its black neighbors even existed.

How many deaths were actually down to the will of this mysterious cult and how many of these were down to Bernabet specifically will never be entirely clear. Nor will we ever know how many unrelated crimes in Texas and Louisiana were bundled in with the case.

Clementine's defense attorney pleaded insanity, but she stood trial and was sentenced to life at Angola State Penitentiary at the age of 19.

Her brother Zepherin and her father Raymond faded from history after these events.

She attempted an escape on July 31, 1913, but was caught the same day. Despite her escape attempt, she was considered a model prisoner. She didn’t, however, serve very long. According to one brief report about the prison, Clementine received a "procedure" that was said to have "restored" her to her "normal condition," and which allowed her to be released on good behavior after serving 10 years.

Many of the facts around this case remain murky, and Clementine’s life after prison is uncertain… then, in 1985, a Louisiana woman visited her 103-year-old great grandmother, who told her the terrifying tale of Clementine Bernabet. After the elderly woman died that same year, a youthful portrait of her was passed down to her great granddaughter. The likeness in the painting was a match for newspaper photographs of Clementine Bernabet. No doubt she had changed her identity in order to escape the infamy of being America's first black female serial killer.

In conclusion there was much that was not known or verified, but in hindsight there was much gathered concerning the victims and the perpetrators.

By April 1912, 49, victims were killed in Louisiana and Texas. The victims were mulattoes or black members of families with mulatto children.

The perpetrators were dark-skinned Negroes who based their choice on what they believed was "tainted blood" because of a biracial member of the family.

It was evident that robbery was not a motive.

On January, 19, 1912, when the Broussard family were slaughtered a note was left behind which read, "When He maketh the Inquisition for Blood. He forgeteth not the cry of the humble —human five."

The police soon realized the crimes were being commited along the stop of the Southern Pacific Railroad line.

Was Clementine Bernabet's eventual confession to early murders, and the connection to a voodoo charm called candja the only motive? A witch doctor assured her that the charm would protect the perpetrators and that "we could do as we pleased and we would never be detected." Such wholesale slaughter seems overmuch just to test the potency of a charm, what is more possible was the cult's core belief, which was they could obtain riches via human sacrifice.

The last murders were committed in San Antonio, and defectors from the Sacrifice Church referred police to the New Testament Book of Matthews with a text that read: "Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit is hew down, and cast into the fire."