The Missing Priestess

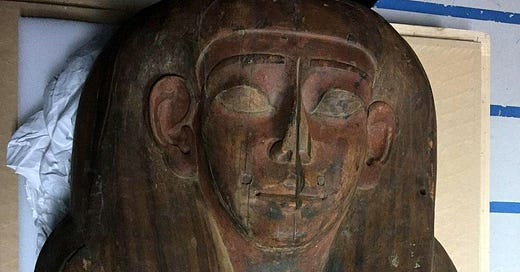

One hundred and fifty years ago a sarcophagus was shipped to the University of Sydney, indicating the carved, cedar coffin was empty.

However when researchers opened it, guess what they found?

During the 1850s Sir Charles Nicholson went to Egypt and Italy to purchase different artifacts. He was the University of Sydney’s first Vice-Provost. In 1860, he donated about 3,000 artifacts that included the four sarcophagus to the university, which eventually were made part of the Nicholson Museum.

One of the four coffins had been marked as empty. According to Jamie Fraser, a curator at the Nicholson Museum: “When I arrived at the University, a catalogue from 1948 said it was empty. But no-one really knew what was inside.”

The item had been stored and forgotten until 2017. The ancient writing that cover the coffin gave the archaeologist the priestess’ name and helped them date the mummy to about 600 B.C. This was the time when Egypt was ruled by native Egyptians. Inside were human bones, which they believe belong to Mer-Neith-it-es (‘Neith loves her father’), a high priestess.

Fraser said, “We know from the hieroglyphs that Mer-Neith-it-es worked in the Temple of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess.”

During those 2,500 years the coffin had lain hidden at Sais, it was ransacked by robbers, and what was left inside the coffin was about 10% of the body, with some bandages and more than 7,000 beads made of faience; glazed beads that the Egyptians believed were instilled with the energy of rebirth. The beads probably made up a net or shawl that covered the body.

The lavish beads and carved coffin made of expensive cedar indicates that the priestess was wealthy or served possibly in the temple of Neith.

It’s not unheard of that mummies would be placed into sarcophagus that didn’t belong originally to them, so it’s not positive the remains belong to the priestess. From a scan completed on the bones it’s been confirmed that she was an adult in her 30s. The scan also revealed that the feet and ankle bones were largely intact.

Inside the coffin was the resin poured into the mummy's skull after its brain was removed.

The goddess Neith was the patron of Sais, which existed on the western edge of the Egyptian delta. Sais was an ancient city that dated back to before 3,100 B.C.

Neith was referred to as the “grandmother of the gods”, however she wasn’t only connected to creation but warfare and hunting. She was also the judge of the dead in the Hall of Truth.

An inscription dating to Roman times found in the temple of Khnum at Esna describes where Neith emerged from the primeval water to create the world. She created the Sun God Ra and his enemy Apophis (Apep). She also created the city of Sais.

Apophis symbolized by a huge snake, who the Egyptians believed would bring about the end of the world, represented chaos and the powers of darkness.

Neith has also been depicted as nursing baby crocodile, and there’s a possibility she was the mother Sobek the crocodile god of ancient Egypt.

However it seems this priestess served the goddess Sekhmet, which is attributed with violent characteristics that can cause destruction and illness. Her name signifies "who is powerful". The follower must please Sekhmet by praying and giving offerings to her statue. If done correctly the goddess would bring peace and help when sick or at war.

Of the 600 statues recovered of Sekhmet the majority were created during the reign of Amenhotep III (1390-1351 B.C.). Amenhotep’s fascination with the goddess were his hopes she would cure him of illness and bring him good fortune.

It’s also believed that so many statues were made of Sekhmet since priests would perform rituals every day to appease her considerable anger.

She was the form Hathor would take when she was angry, and she became Sekhmet the Bloodthirsty who fed on the blood and fear of her enemies. Eventually both goddesses developed independently with their own identities and attributes.

Sekhmet is sometimes referred to in Egyptian texts as “She Before Whom Evil Trembles”, the “Mistress of Dread”, “The Mauler”, or the “Lady of Slaughter”. During military campaigns, the hot desert winds were considered to be the breath of Sekhmet. Making the goddess angry was known to bring plagues and diseases upon those who dared provoke her.

At some of the temples she was offered the blood of recently sacrificed animals, in order to placate her rage and contain her anger.

The taste of blood satiated Sekhmet and every year when her feast day was celebrated, Egyptian drank beer stained with pomegranate juice to imitate blood. Records of these feasts describe how they would worship “the Mistress and Lady of the Tomb, the Gracious One, Destroyer of Rebellion, Powerful with Enchantments.” Sekhmet’s fearsome reputation came about because she had threatened to wipe out humanity, and what had stopped her was that she got drunk on beer dyed red as blood.

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead in her effort to keep balance between life and death she resorted to population control through plagues, which were called messengers or slaughterers of Sekhmet. A passage of The Story of Sinuhe said that the fear of the king “overran foreign lands like Sekhmet in a time of pestilence”. This is because she was known as “Lady of Pestilence” and the “Red Lady”, alluding not only to blood but to the red land of the desert.

Bastet was the alto-ego of Sekhmet who was the tame, good goddess, while Sekhmet was the Bloodthirsty, the chaotic and dangerous deity of war and love.