THE MARTYRS' BONES IN AMERICA

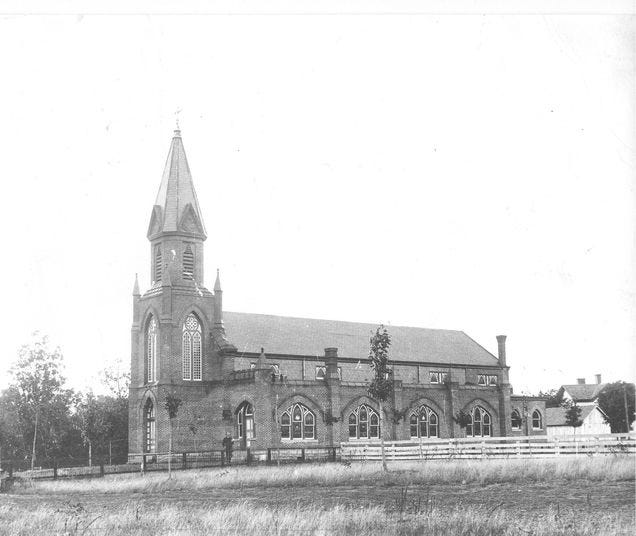

St. Martin of Tours in Louisville, Kentucky was built in 1854. Few people know that the skeletal remains of Saints Bonosa and Magnus have been on display here since 1902.

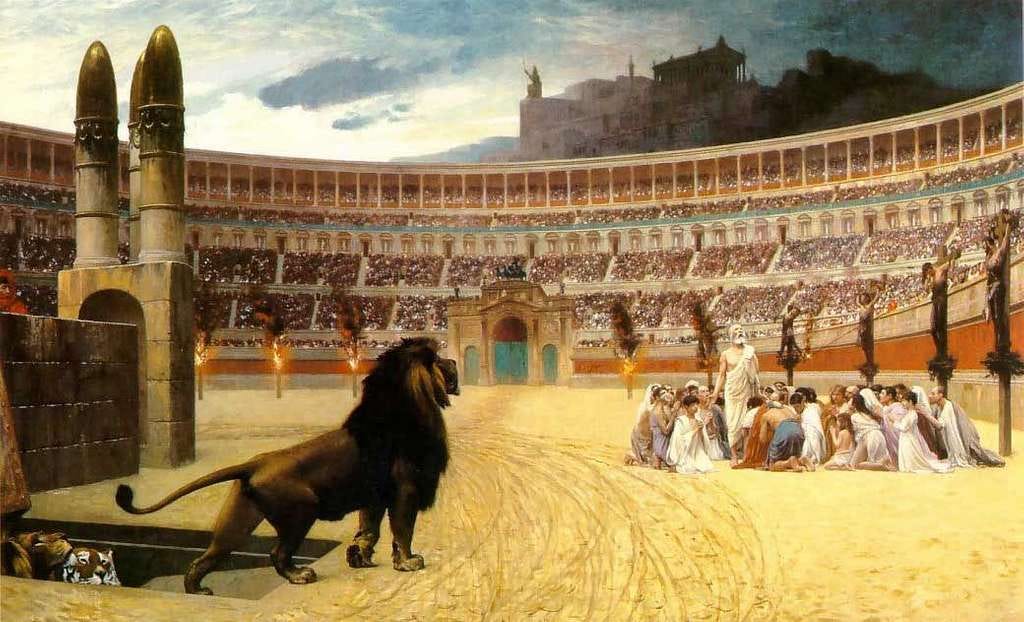

Magnus, a Roman centurion, and Bonosa, a Roman virgin, were put to death in the Roman Colosseum at the height of the persecution of Christians in Rome. Few would imagine that hundreds of years later they would be here in the United States.

Both of them were believed to have been martyred under the reign of Septimius Severus in the 3rd century, or Diocletian in the 4th century. During this time, Christian men, women and children were brought for sport to the Colosseum. One story is that Magnus who was a Roman centurion witnessed when Bonosa was being killed. He was so moved by her courage that he converted, and eventually he faced the same fate.

A description near the shrine says Magnus was martyred with 50 of his soldiers, and as a centurion he had 100 men under his command.

Another version is that he stepped into the ring to save the young girl and was killed along with her.

The exact date of their death is uncertain. The date 308 is etched into the marble top of St. Magnus’ sarcophagus. And the date 207 appears in a brief history printed in a book celebrating the centennial of St. Martin parish in 1953. The spelling of Bonosa has also been written as Bonoza.

The martyrs’ remains were interred in the catacombs of Pontiani, Italy and rested there until 1700, when the Cardinal-Custodian of Holy Relics entrusted them to the Cistercian Nuns of Agnani, in the hills east of Rome. The relics were venerated there for nearly two centuries in their resting place beneath an alter. This changed when the Italian government confiscated the monastery and forced the Sisters to leave.

When the Italian government seized the church in Agnani, Pope Leo XIII gave the relics to St. Martin of Tours in Louisville at the request of Msgr. Francis Zabler, in charge of the church at the time. The diocese received the bones around 1902, and the body of each saint was placed in a glass reliquary on each side of the altar; St. Bonosa on the left and St. Magnus on the right.

Fast forward to 2012, when St. Martin needed to refurbish the side altars of the church. The parish decided to repair the glass sarcophagi as well. The parish also chose to have the bones examined since it didn’t have an official history of the remains.

Philip DiBlasi, an archaeologist from the University of Louisville volunteered to do the forensic analysis of the bones. He soon found that the features of the skeletal remains corresponded to historical accounts of the saints.

St. Magnus’ skeleton was only about 45% complete and most of the bones were fragmented. The cranium was intact, but the mandible was missing. According to his analysis, the remains belonged to man of mixed ancestry, mostly Caucasian with some Mediterranean/African characteristics, who was between 45 and 50 years old when he died.

St. Bonosa’s remains were in a much better state. Her skeleton was 95% complete, and both the skull and pelvis were present. His examination found the bones belonged to a woman of Caucasian ancestry who was about 24 years old when she died, and stood between 5’ and 5’6” tall. He also found squatting facets at the bottom of her leg bones (tibia) and foot bones (talus) and indications that she was right-handed.

The relics of Saints Bonosa and Magnus were wrapped in robes and transferred to the repaired reliquaries during a ceremony on September 9th, 2012.

During the work on the altar, workers discovered another little interesting piece of history during their repair work. At least part of the sanctuary floor is supported by street car rails.

In 2019, a man broke into the church and vandalized the main altar. He was subdued and was described by the church’s pastor as "obviously troubled". Since the 1960s this area of Louisville has slowly become more crime-ridden.