THE GREAT DEATH PIT AT THE ANCIENT CITY OF UR

Dating back about 4,600 years, the Great Death Pit at the ancient city of Ur, in modern-day Iraq, contains the remains of 68 women and six men, many of which appear to have been sacrificed.

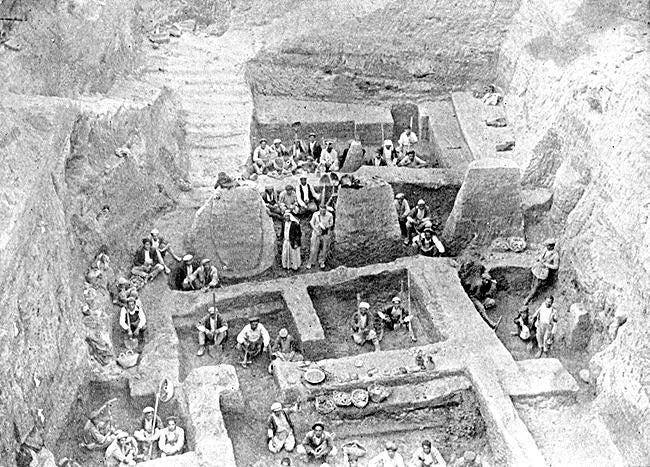

In 1922, Sir Charles Leonard Woolley led a team of archaeologists from the British Museum and the Pennsylvania Museum to explore the great ziggurat at Tell al-Muqayyar or Ur (its biblical name). He continued his excavations for 12 years.

His greatest discovery was the so-called "Royal Cemetery". The cemetery was built outside of Ur's city walls. The city remained abandoned after the Euphrates River changed its course more than two millennia ago. Later the walls of Nebuchadnezzar's city was built over it.

Woolley found two mass graves, or “death-pits” as Woolley dubbed them, containing gold-and silver-adorned skeletons. One rested on top of the other. The upper graves dated to the time of Sargon of Akkad, first ruler of the Akkadian Empire.

Close to 2,000 burials were found dating from 2600 to 2000 B.C. Both royalty and commoners were buried there. Some bodies were rolled in a mat, others were laid to rest in domed tombs.

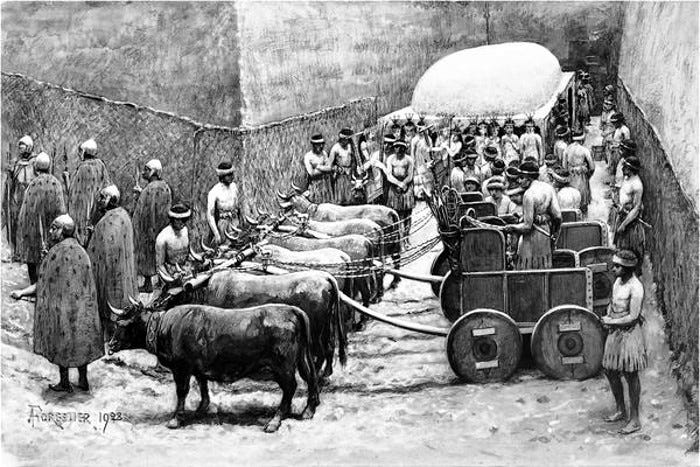

The sixteen "Royal Graves" were easy to identify, not only because of the richness of the goods left inside them, but because of the attendants sacrificed to serve their masters in the afterlife.

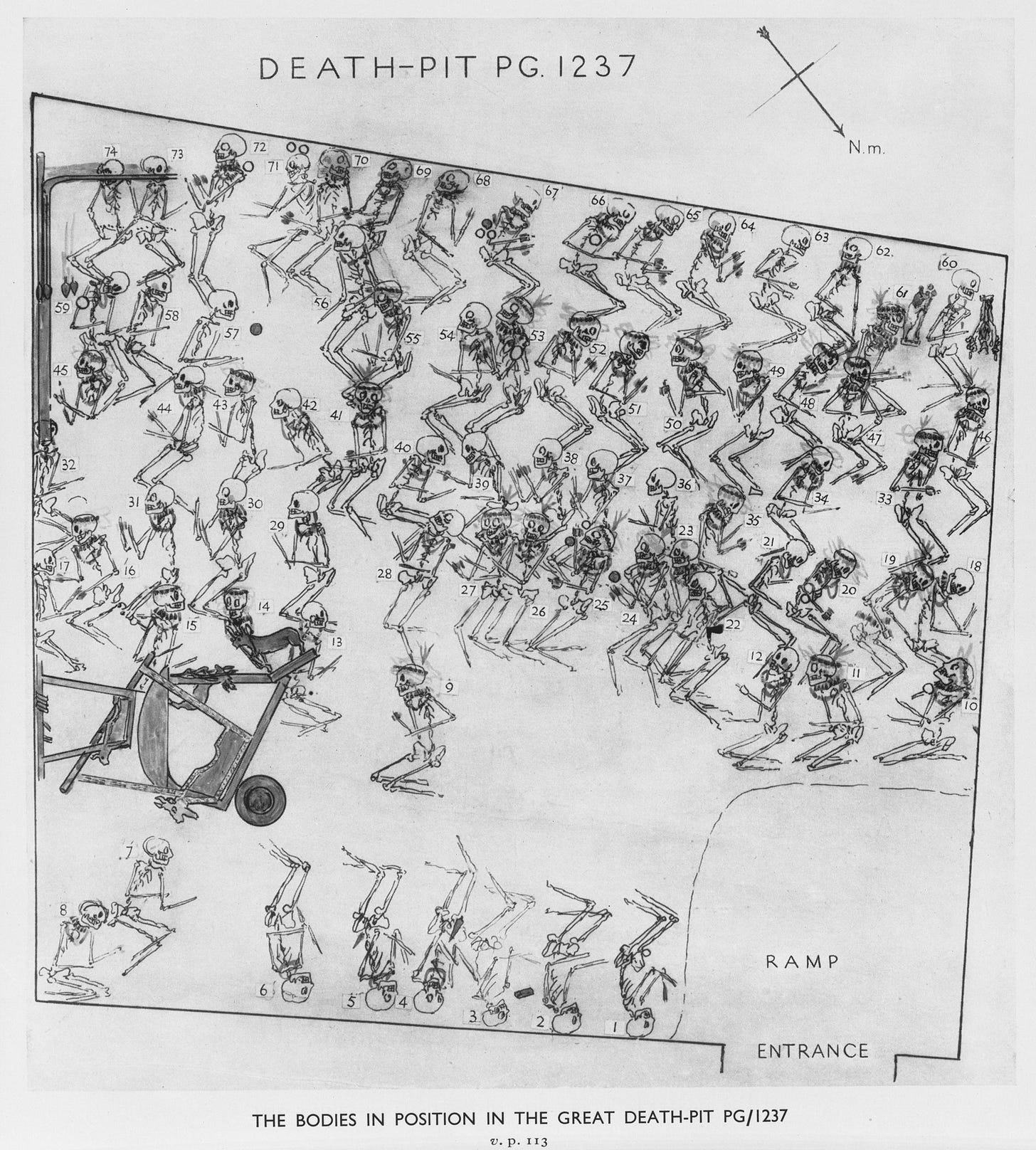

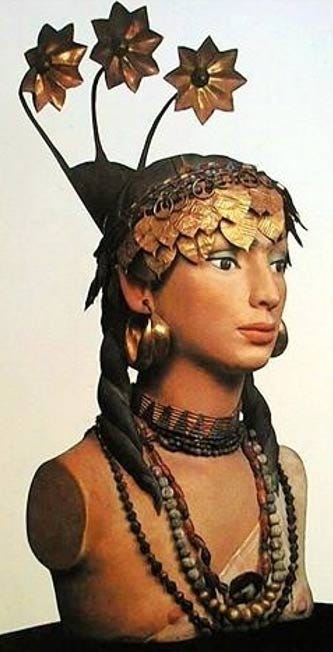

The most spectacular of Ur's royal tombs was PG1237 with 74 attendants, which Woolley dubbed "The Great Death Pit" since there was no tomb inside it. Six men were placed near the entrance to guard against grave-robbers. They held weapons of silver and gold, along with the insignia of their rank. Sixty-eight women, dressed in scarlet were lined up in four rows in the northwest corner of the pit. They wore headdresses and jewelry made of silver, gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian. They had cups or shells holding cosmetic pigments. Six women near the southeast wall were placed by two lyres and a harp.

Half the women had cups as if they were at a banquet, but the men had nothing. One women was still clutching her headband.

Body 61, in the right corner was a woman more elaborately dressed than the rest, and she had a silver tumbler next to her mouth.

It's unknown if the attendants voluntarily took poison and were buried alive while unconscious, or if they were dead when the tomb was sealed.

Another tomb, PG 789 brimmed with the bodies of 63 individuals.

Woolley believe the attendants were not killed due to the neat arrangement of the bodies. No doubt they were promised a place of importance in the afterlife. In reality the men were commoners and the women were servants, so this would have appealed to them.

However a study completed at UPenn Museum on the skull of a woman and a soldier, showed signs of pre-mortem fractures inflicted by a blunt instrument. This would have killed them, not poisoning.

Perhaps those who did not die by poisoning were bludgeoned to make sure they were dead before the tomb was closed.

Another alternative is that instead of poison the attendants were given a sedative. Clubbing them to death was planned, but this would have to be evident on all the bodies, which have yet to be examined.

The most unusual thing about this burial is the absence of a king or queen. Some believed Body 61 is Queen Pu-abi because of her elaborate dress. However she wasn't buried with cylinder seals, she didn't have her own personal possessions and she wasn't placed on a funeral bier inside her own chamber.

Her body lies in a jumble with other women, with nothing but her superior jewelry to indicate she had greater status then the others. Perhaps she could have been a favored concubine.

Oxen used to pull carts were also sacrificed.

The most stunning discovery from The Royal Tombs of Ur was the burial chamber of Queen Pu-abi, which luckily had not been looted.

There is speculation if she was actually a queen since since she's referred to as a nin or eresh. The former means "lady, a noblewoman", the latter means "queen". Since only women of nobility could be a high priestess, this also could have been her position. It's clear she held a high status due to the number of people sacrificed to serve her, as well as the richness of the grave goods.

She measured less than five feet in height and was about 40 years old when she died.

Two goat statues were found in PG 1237. Referred to “ram in a thicket” by Woolley which were made of wood and covered in gold, silver, shell and lapis lazuli.

In 1930, Woolley wrote Ur of the Chaldees detailing the discoveries that had been made on the site.

In 2008, a team of scholars, found that the walls of the royal tombs were beginning to collapse, mostly due to neglect. For 30 years the Iraq Department of Antiquities did not have the resources to conserve the site.

There is no escaping the fact that in ancient Mesopotamia not all lives were valued the same. Whether these servants met death willingly due to what was promised in the afterlife, or if they were murdered to ensure the elites of the city had someone to serve them still remains a question unanswered.