The Forgotten Little Girl

Construction workers made a macabre discovery May 2016, when they were renovating a garage for a home located in Sn Francisco.

It was a small thing, measuring a little over 3 feet. It could have been mistaken for a treasure chest, except for the placid face seen through two windows on the lid of what in reality was a coffin, once a metal plate was unscrewed from the top of it. The blonde toddler girl seemed to be asleep, perfectly preserved by her airless resting place. She wore a white christening dress with hand-stitched lace and baby booties. She held a purple nightshade flower in her right hand, sprigs of lavender had been braided into her hair and a rosary of eucalyptus seeds lay on her chest. There was nothing to identify her.

She was believed to have died around 1870, when pinewood coffins sold for $2. Her elaborate glass and cast-iron vessel would have cost 10 times that much. It seemed she was a cherished child from an affluent family.

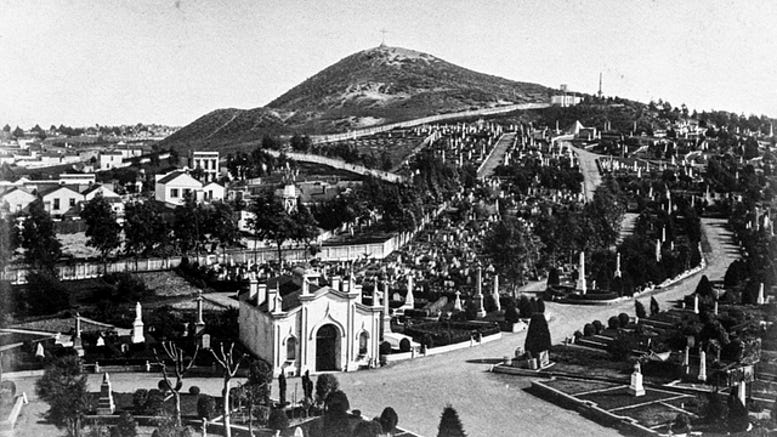

Historical accounts describe where the city grew around San Francisco Bay. What is now the financial district was a cemetery, but with the discovery of gold in 1849 the demands of the living as always, outweighed the dead’s eternal sleep. The bodies were relocated west, closer to the ocean.

In the 30-some-odd years after the Gold Rush, dozens of the city’s cemeteries were full. Between the 1880’s and the turn of the century the dead were once more evicted, and thousands were exhumed and reburied in Colma. Richmond District where the child was discovered, did not receive anymore burials after 1901, but eventually there was an order to move the coffins.

Research has found that the workers just dug trenches and unearthed bodies they came across but did not refer to maps or blueprints.

The removal contractors placed string lines in an east-west orientation, spaced where experience told them the most graves would be intersected. Experts moved along those string lines, probing with hardened brass rods at set intervals. They could literally predict by feel and experience whether there was a casket, a collapsed grave, ashes or no grave at all below. Workers dug only where they marked and as deep as they marked. Everything was done by hand.

This was not the only instance of human remains left in ground instead of being reinterred in a cemetery. In September, 1993, crews were working on a new addition to the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, site of the Golden Gate Cemetery in Lincoln Park, when they came across at least 60 redwood coffins. The death and burial records from the period were lost in the 1906 fire, and it was theorized the laborers just came through and kicked over the headstones on the graves instead of moving them. Work crews also found bones from cadavers used for dissection in the medical school. It was estimated most of those interred here came to San Francisco during the 1849 Gold Rush. Ultimately 700 graves were unearthed.

It was inevitable that homes, businesses and parks would be built on land that was once littered with tombstones. One of them was the house on Rossi Avenue which the Karner family had owned since 1976. The family was well acquainted with the history of the Richmond District where they lived, but they were still surprised when they received a phone call from the workers tearing out their garage floor. The family was vacationing in Idaho, and the photos the contractor sent left no doubt about what they had found.

The San Francisco medical examiner came to the home, unsealed the casket, verified it was a human body, and left it without taking the case. As far as they were concerned this was a legitimate burial. The question was that since the city had left the casket behind in the first place, should they still be responsible for its final disposition?

The child’s body began to decompose rapidly once the casket was unsealed. The city referred the Karners to Elissa Davey of the Garden of Innocence, an organization that buries abandoned children. They secured the funds to rebury the girl in Colma.

A lock of hair from her bangs was cut to be used as a sample of nuclear DNA which would provide genetic information from both of her parents. Her maternal ancestry was rare; anyone who has this DNA signature is from the British Isles.

Less than 100 yards from where the girl in the casket was found, a tombstone from the same area was found. Research indicated that this was probably part of the Odd Fellows Cemetery in use from 1860 to 1901. Using a map from 1900, it was determined she was buried in the Cosmopolitan section of the cemetery in what was probably the family plot. Records had thousands of names, and when the search was narrowed down there were dozens of burials that matched the child’s.

Elissa Davey and the Karner’s two young daughters decided to giver her a name so that she would not be buried in anonymity. Several weeks after she was found dozens of Bay Area residents, members of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows and Davey's colleagues gathered at Greenlawn Memorial Park in Colma. The little glass and cast iron coffin was sealed inside a new cherry wood one. A heart-shaped headstone made of granite was etched with the name Miranda Eve with the epitaph “If no one grieves, no one will remember.” The other side was blank, kept this way so that her true name would hopefully be etched there.

A year later, the mystery of her identity was solved. Her name was Edith Howard Cook, born in San Francisco on November 28, 1873. Her parents were Horatio Nelson Cook and Edith Scooffy Cook. She died on October 13, 1876, of marasmus a disease characterized by a severe deficiency in nutrients, particularly protein, and can be brought on by viral, bacterial or parasitic infections.

The girl’s DNA was matched to that of a descendant now living in San Rafael.

A map of the cemetery’s development in 1865 was found, and overlaid over the residential neighborhood. This narrowed down the search to two girls. Birth, marriage, death and property records were reviewed until the right family was found.

Peter Cook, 82, a grandson of Milton Cook, Edith’s older brother supplied the link they needed. A team took a swab of his saliva for DNA and the comparison with Edith’s turned up a 12.5% match along unique genomes that can be identical only along direct descendants.

Sadly Peter's father Horatio Nelson Cook II, committed suicide in 1937, when he was 33 years old. He was found hanging in his office from a piece of round belting manufactured in the plant he ran.

Before her birth, Edith’s parents had welcomed a son they named Milton, and after her death they had another son, Clifford and a daughter they named Ethel.

The Cook family was prominent in San Francisco in the late 19th century and early 20th century. The Scooffy side of the family were pioneers in San Francisco who arrived with the Gold Rush.

Edith’s grandfather was Peter Scooffy, an oyster merchant who immigrated to the U.S. from Greece through New Orleans. There, in 1845, he married Martha Bradley, whose family lineage traces back to the earliest Virginia settlers. The couple moved to San Francisco, where they eventually had Edith’s mother.

Edith’s paternal grandfather, Matthew Mark Cook, was English and her grandmother came from Nova Scotia. They moved to San Francisco years after the Scooffy family, and had seven children. One of them was Edith’s father, Horatio Cook.

Together father and son established the family business, M.M. Cook & Son, a leather belting and hide-tanning business. After Matthew died, Horatio Cook continued to run the company with his sons (Edith’s brothers,) Milton and Clifford, and renamed the business H.N. Cook Belting.

The company remained in existence until the 1980s, when it merged with Hoffmeyer Belting and Supply Co. in San Leandro. The new business was then bought by San Diego Rubber Co. Inc. in 1994 and renamed Hoffmeyer Company Inc.

Edith’s younger sister, Ethel grew up to become a San Francisco socialite. She married two millionaires. The first was Sterling Postley (1899) and Ross Ambler Curran (1911).

In her father-in-law's obituary in 1908, it was mentioned she was living with Sterling in Paris and she had been toasted as a great beauty by the Grand Duke Boris of Russia. Contrary to her sister Edith, Ethel had black hair and gray eyes. She had danced with the Duke at a ball before her marriage, and it was circulated they were engaged, which they were not.

It turns out that Ethel's trip to Paris was to seek a divorce and by 1910 it was secured. She had one child with Sterling, a son Clarence Postley, and she told the newspapers it was an amicable divorce.

In 1911, Ethel really set tongues to wag when she married Ross Curran who was once married to Elsie Postley, her one time sister-in-law. It was understood that Ross and Ethel had known each other for several years, when they were each married to one of the Postley siblings. In other words, was this romance the catalyst that ended their respective marriages? Ethel divorced her second husband in 1933, and she died in 1935 at the age of 57 from a heart attack. She had outlived her three siblings. Her son Clarence Postley died in 1983.

Peter Cook has eight children, 13 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren, and he was surprised when he learned he was related to the mystery girl buried in San Francisco.

Since Edith’s identity search began, the remains of three other people buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery location have been discovered and need to be identified, Davey said.

Little Edith's Ghost

At least twice in recent years, Ericka Karner said, she and her husband have heard the inexplicable sound of children’s footsteps running in the home. The couple have two daughters, but the children were sleeping or not where the steps were heard in both cases, she said.

Even after Edith’s body was found, disinterred and moved, the spooky steps still could be heard, Karner said. “We had a couple of contractors, on separate occasions, who thought they heard footsteps,” Each time, the contractors walked through the house looking for a child — possibly a wayward kid who had run into the house from a park across the street — and both times, the contractors found nothing.

“I’m not sure where I stand on where the soul goes, but my hope is … if she was still hanging around here figuring out where she needs to be, that her being identified will give her a little peace and she’ll potentially go off and be with her family, where she needs to be,” Karner said.

Around 1920, is when 26,000 remains from the Odd Fellows Cemetery in the Richmond District were moved to Colma’s Greenlawn Memorial Park. Edith’s mother had died the year before, and her father in 1891. These were the two persons who perhaps would have made sure Edith was exhumed and laid to rest in Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in Colma, where all her family’s graves are. The dead are only remembered by the living.