Murder, Cannibalism and Voudou

In 1864, four men and four women were executed in Haiti for the murder of a girl that was later cannibalized. The claims were that a voodoo priestess had ordered the sacrifice.

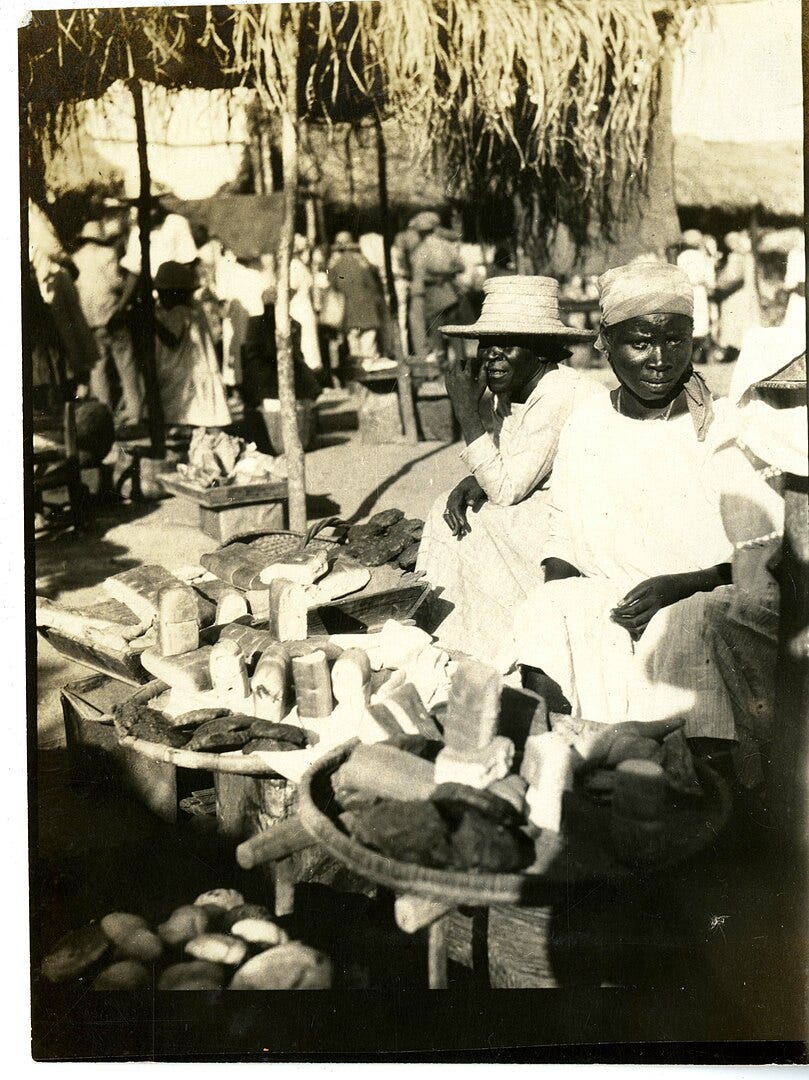

February 13, 1864 was Saturday in Port-au-Prince, Haiti which was traditionally market day, but on this occasion French-educated Haitians rubbed elbows with illiterate farmers for another reason in the market square. It was the day chosen by President Fabre Geffrard (1806-1878) for the execution of 8 high-profile prisoners.

Gossip was rampant, and even villagers who had to travel for a day, came to view the spectacle.

Geffrard was trying to pull his country out of the backwardness of its African past, and the rampant belief of voodoo (vaudaux, vandaux, vodou). The practice had arrived with the slaves centuries before, and flourished in the maroon villages and plantations of the interior where priests seldom visited.

In 1791, it was believed a secret voodoo ceremony was the spark for the violent uprising that ousted the French from the country. Around 75,000 white French people died during the Haitian revolution. Between January to April, 1805, 3,000 to 5,000, white Haitians were practically eradicated.

Only three categories of white people, except foreigners, were selected as exceptions and spared: the Polish soldiers who deserted from the French army; the small group of German colonists invited to the north-west region before the revolution; and a group of medical doctors and professionals. Reportedly, also people with connections to officers in the Haitian army were spared, as well as the women who agreed to marry non-white men.

Hesketh Hesketh-Pritchard (1876-1922) a British explorer and adventurer who walked across the Haitian interior in 1899, described the belief as “West African superstition serpent worship” and that believers indulged in “their rites and their orgies with practical impunity.”

Due to newspaper reports through the years, outside Haiti voudou was described as primitive. This specific case was often referred to, which brought the belief system into disrepute.

The murder had taken place in the village of Bizoton, outside of Port-au-Price. It later became known as the Affaire de Bizoton.

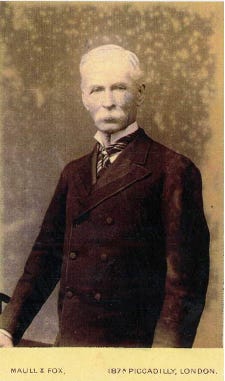

The group of believers were called the Vandoux Sect, or the members of the Law of the Adder or Serpent, instilled by Emperor Soulouque.

Faustin-Elie Soulouque (1782-1867) had served as president and then emperor of Haiti from 1847 to 1859. He created a secret police and was a vodouisant who maintained a staff of bokors and manbos.

The tenets of the sect was the adoration of the serpent (il Couleuvre), blind obedience, keeping the secret of the mysteries, dancing while intoxicated around the Holy Arch of the Serpent, sacrifice to the Serpent of she-goats, fowls and possibly children. It seemed contradictory that the worshippers of the Serpent were all Catholics who attended church, prayed the Rosary, adored the holy relics, burned candles before the images of the Holy Virgin and used Holy Water.

The leader of the group was called Congo Pelle (pelle is French for shovel), who claimed he had received an order from the "Vaudoux god" that an offer should be made of a human. He resolved to sacrifice his niece Claircine, daughter of his sister Clair Pelle. His assistant was another sister named Jeanne Pelle, who lured the child’s mother away on a pretext to visit Port-au-Prince. Jeanne was a mamanloi and the daughter of a priestess.

On December 27, 1863 the child who was about 12 years old was abducted, and taken to the house of Julien Nicolas. Other adepts, Floreal, Guerrier and Beyard waited there. They tied the child up, and placed her in a place called "Humfort" which is the name of a Vaudoux temple. They were said to be found in every district of the country, and hung with various Catholic emblems.

The child was placed beneath the altar, and kept there for four days. On December 30 at 10 o'clock at night she was taken to the house of Congo Pelle for the ceremony. Her aunt held her waist, Floreal strangled her while others held her legs and arms. Floreal skinned the corpse with a knife and cut off her head. They caught her blood in a jar, and the flesh was cut from the bones and placed in large wooden dishes. Jeanne Pelle, Floreal, Guerrier, Congo Nereine (wife of Floreal), Julien Nicolas, Roseida Sumera and Beyard went to Floreal’s house, where Jeanne cooked the flesh with Congo beans (pois congo). Claircine's head was boiled with yams, and they ate the fleshy parts.

The defleshed skull was placed on an altar, where the adepts circled it and danced while singing a sacred song.

Once the ceremony had ended the child’s skin and entrails were buried near Floreal's house. The remaining bones were reduced to ash and pulverized in order preserve it.

They agreed to meet again on January 6 (Feast of the Epiphany) when a new sacrifice would be offered. They had taken another young girl named Losama, whom Nereine one of the followers, had stolen on the main road of Leogane.

When Claircine's mother made inquiries about her daughter's whereabouts, along with the disappearance of the other girl, police searched Floreal's house, where they found the discarded, freshly-boiled skull. Then they found the other girl bound under the altar, and other remains of Claircine.

The group was arrested, and a jury found them guilty in February, 1864. It was suspected they had killed other children as sacrifices.

After the trial and execution there were discussions on how much Claircine’s mother knew of the plot, and if she had actually allowed the child to be taken. However since the prosecution used her testimony against the accused, it was thought wise not to question her too much on the subject.

Once the crime became known, there was so much indignation from the general populace that a military force had to be used to keep the people at a distance.

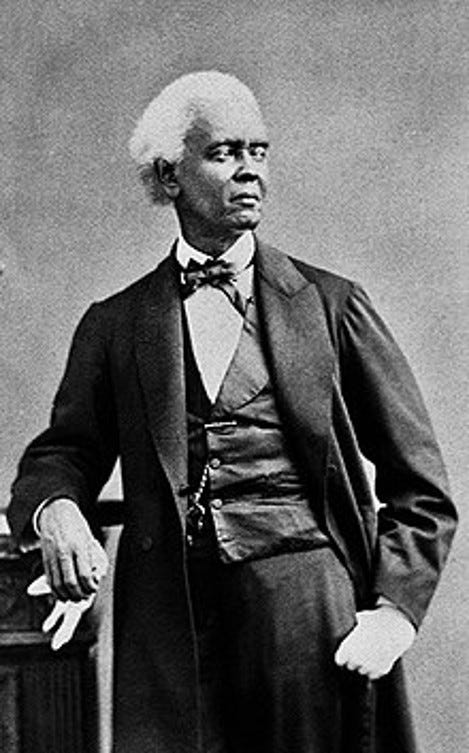

No transcripts of the trial were kept, and Sir Spenser St. John the British charge l’affaires in Port au Prince at the time kept a detailed account since he attended the proceedings, in which he said he had “made the most careful inquiries”.

He described Congo Pelle (Pele) as a “laborer, a gentleman’s servant, and idler” who had grown resentful of his poverty. His sister (Jeanne Pelle) was a vodou priestess, who offered him the solution which was to propitiate the serpent with a sacrifice at the turn of the new year. A consult was made with two papalois, Julien Nicolas and Floreal Apollon, as to what would be an appropriate sacrifice, and they indicated he should offer up the “goat without horns”—a human sacrifice.

After the trial Haiti’s Code Penal increased fines for “sorcery” and added that “all dances and other practices that… maintain the spirit of fetishism and superstition in the population will be considered spells and punished with the same penalties.” President Geffrard attempted to curb public nudity which was common in the interior and a 99% illegitimacy rate, that was accompanied by “bigamy, trigamy, all the way to septigamy.”

During those years, the rural folk were strong believers in voodoo. The local people who lived in the capital and had betters means, and who tended to be French-educated and of mixed race, thought vodou was holding Haiti back. It was associated with the slave rebellion, and was the faith of the most brutal and backward of the country’s rulers.

Sir Spenser described that, “all the prisoners had at first refused to speak, thinking that the Vaudoux would protect them.” Finally Roseide Sumera admitted she ate “the palms of the victim’s hands as a favorite morsel.” The others in the group tried to keep her silent, but her story was used by the prosecution as witness testimony.

Other witnesses who had not participated in the murder, a young woman and child who watched from chinks in the wall of an adjoining room, also testified to what they saw. The child’s testimony was especially compelling as it seemed she had been intended as a second victim.

St. John described where she was found tied up under the same altar that had hidden Claircine. Human sacrifices were offered at Easter, Christmas, New Year's Eve and especially on Twelfth Night or Les Fetes des Rois. She was the intended sacrifice for Twelfth Night (January 5), which was the most sacred date in the vodou calendar. The young woman who was with her, which in truth was set to guard the child, eventually confessed to eating leftovers from the feast the following morning, thus making her as much a cannibal as the others.

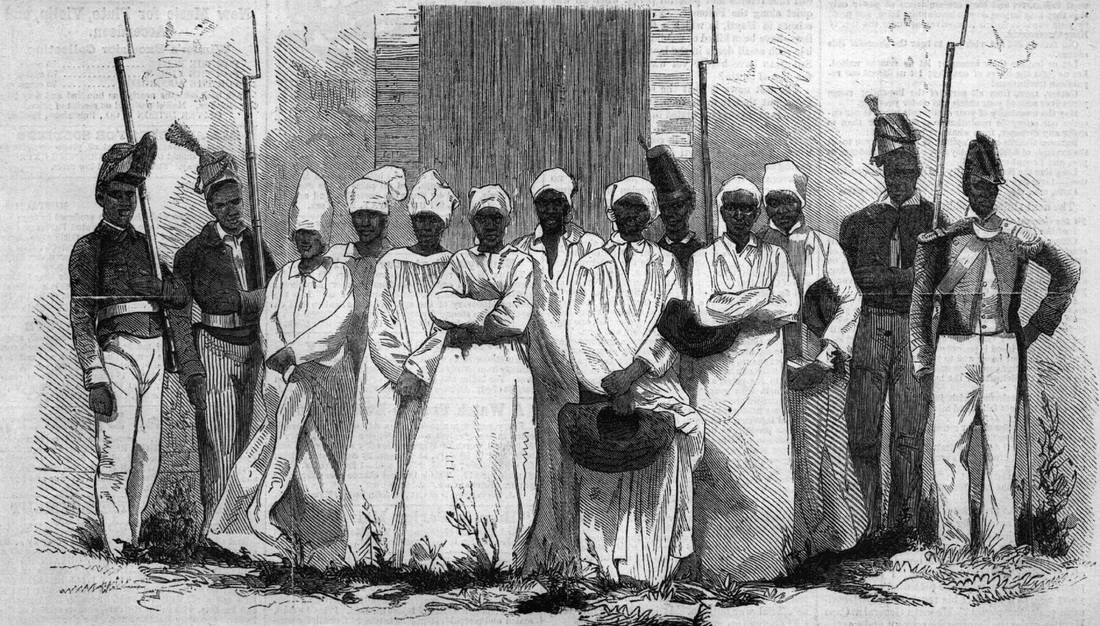

The eight who were brought to trial were Julien Nicholas, a papaloi; Floreal Apollon another papaloi; Guerrier Francois and Congo Pelle. The women were Jeanne Pelle, a mamanloi, Roseide Sumera, Nereide Francois and Beyard Prosper.

They were dressed in white on the day of the execution, and were tied in pairs where five soldiers fired at them. They were so inaccurate that only six fell wounded on the first discharge. The men were so untrained it took them 30 minutes to complete the execution.

The bodies were guarded but not so well, since in the morning the two papaloi and the priestess' body had disappeared.

In 1909, John T. Driscoll charged that “authentic records are procurable of midnight meetings held in Hayti, as late as 1888, at which human beings, especially children, were killed and eaten at the secret feasts.”

St John described where he attended a dinner where the Archbishop of Port-au-Prince told a story that occurred in 1869. A French priest in charge of the district of Arcahaie persuaded some of his parishioners to take him to the forest, so he could witness what happened during the Vaudoux ceremonies. They blackened his hands and face, and disguised him as a peasant. He mixed with the multitudes that gathered from the surrounding area. He saw a white rooster and a white goat killed, and the animals' blood was used to mark those present. After a young man asked for a favor from the priestess, she instructed him to bring forth the goat without horns.

The crowd in the shed separated, and there was a child sitting with its feet bound. A rope passed through a block was tightened, and the child was pulled towards the roof by its feet. The papaloi came forward with a knife. The Catholic priest was held back by the parishioners who had taken him, since they he knew he meant to intervene. They carried him from the spot, and even though there was a short pursuit, he made it safely back to the town.

He went to the police but they would do nothing. In the morning they went to the location of the sacrifice, and found the remains of the feast and the boiled skull of the child.

Surprisingly the authorities at L'Arcahaie were upset at the priest, and under the pretense that they could not protect him, sent him to Port-au-Prince where he made a report to the archbishop.

St. John referred to a communication that appeared in Vanity Fair on August 13, 1881 by a reply published at Port-au-Prince in a Haitian journal, L'Ceil.

It described herb-poisoning and antidotes, and of midwives who rendered newborn babies insensible, then buried them, dug them up, restored them to life and then ate them. In May 1879, a midwife and another were caught near Port-au-Prince eating a female baby, and a Haitian of good position was found with his family eating a child. The women were punished to six weeks in prison, and the family man to one month. Fear of the vaudoux priests was blamed for the light sentences.

An English doctor bought and identified the neck and shoulders of a human in the market at Port-au-Prince. In February, 1881, at St. Marc a cask of pork was sold to a foreign ship. When fingers with fingernails were found in the cask, is when it was discovered the flesh belonged to a human and not a pig.

In 1884, St. John claimed that since the reign of Soulouque, professional authors were paid by the Haitian government to spread "rose-tinted accounts of the civilization and progress of Haiti. But twenty-four hours in any town of that republic would satisfy the most skeptical that these semi-official accounts are unworthy of belief."